As the only Few for Change member who had never been to the Comarca, I always felt like I was missing a crucial part of the experience. While my final research project in Panama focused on education and I am a firm believer in education as a method for fighting poverty, I still felt like I couldn’t quite relate to our scholars and to the Comarca in the same way that the rest of the organization could. I was inspired by what I had read in the students' applications and was moved to help these young leaders receive an education, but I had no faces to put to the communities that I heard the rest of the Few for Change team talk about.

Arriving at the Comarca, not an easy task

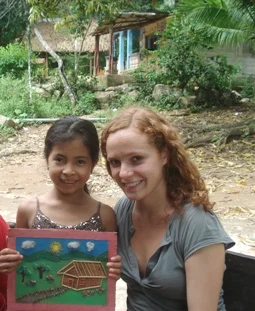

When I found out I would be traveling to Panama on a family vacation this summer with my mom and brother, I decided I had to visit the Comarca. Few for Change Co-Director Gillian Locascio met us in San Felix and was our very gracious host for the day that we spent there, bringing us all the way into her community, Rincon. Rincon is a small community about an hour truck ride and then a two hour walk from Quebrada Guabo, the border town at the edge of the Comarca. Beginning with the transportation, the lack of infrastructure was one thing that really shocked me. I had heard about this in our team meetings, but I guess I had to see it for myself before I could fully understand. There are roads that run as far in as Rincon, but there are very few cars that pass that way, and there are many communities farther in that have even less transportation available. Health services also become more limited as you move inward, with some centrally located health centers and then smaller health posts that are generally staffed by one person that often lack even the simplest supplies. When I was in Rincon, the health station there had recently run out of bandaids.

Barriers to education: learning on an empty stomach

"I’m not sure if I would have made it through middle or high school if I had to fight as hard as these kids to get an education. "

Along our journey, we saw many different groups of children walking to or from school. Those who are lucky enough to live near a school may have a short walk, but some of them have to walk up to three hours to get to school every day. Gillian explained to us that they walk three hours, and once they get there, the school does not provide them with lunch so they have to walk back three hours without eating anything all day. Sometimes they get sent back home if they don’t have the “proper” uniform on, which could mean something as small as wearing the wrong sock. I had always taken my education for granted; even after high school it was just assumed that I would continue on to college, and that my family would make sure there was a way for this to happen. I’m not sure if I would have made it through middle or high school if I had to fight as hard as these kids to get an education.

Determination in spite of "red tape"

Since leaving the Comarca, I have been thinking a lot about different types of poverty. Last summer, I worked in some very poor communities in Nicaragua. At first glance, these communities were far worse off than Rincon and the other communities we drove through in the Comarca. Their houses were made out of plastic and cardboard instead of wood or cement. They often did not have enough food to eat, whereas the Ngobe grow a lot of their food and thus appear to have more. They were, however, situated close to larger cities, and therefore had the advantage of being closer to water systems, health centers, transportation and schools. One thing they had in common, however, was the extreme ability to take initiative. I saw this in communities in Nicaragua, but I was still very impressed by the level of initiative in the Comarca. Gillian talked a lot about work parties and how the community would come together on a given day to get a job done, knowing that it would be easier with more people. These work parties seemed to be the norm for anything ranging from building a house to clearing land to building ponds to raise fish. Another thing I found shocking was the number of community projects that had been killed by bureaucratic problems and “red tape”. There was a latrine building project that was in line to be funded but the materials never showed up. There were multiple projects that were shot down because the community’s proposal did not fit the exact requirements for the grant, often a result of guidelines that were absurdly specific and not at all realistic, such as building using certain materials that are not readily available in the Comarca. There was a road that was built so children could get to school more easily, but the government awarded the project to the lowest bidder, who then built a road that eroded a lot of the land and became almost unusable during the rainy season.

Commitment to education, despite the odds

"[The students'] commitment to education despite all the odds is absolutely amazing..."

As discouraging as all of this is, the people of the Comarca haven’t given up. This level of determination that I saw in the adults is the same determination that keeps our scholars going to school, despite their lack of transportation and funds. Their commitment to education despite all the odds is absolutely amazing, and is something that I greatly admire. I knew that the work of Few for Change was important before my trip, but it took a 2,000 mile flight, a 6 hour drive across Panama, an hour truck ride and a two hour walk for me to realize just how important it truly is.